City relives Mother’s memories on celluloid

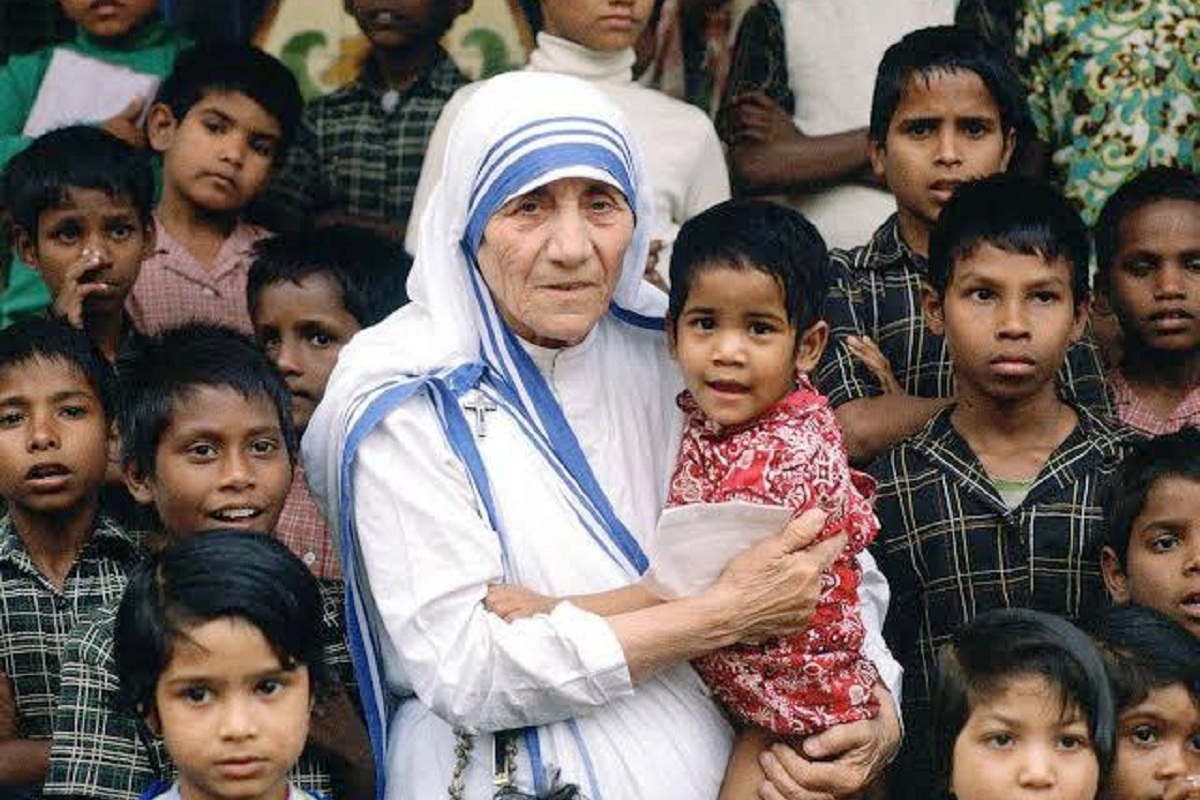

Mother Teresa, who attained sainthood for her work for the downtrodden and the marginalized sections of the city

Today, on her 111th birth anniversary we need to be reminded how and where she began her life’s work. She had enlisted as a Loreto nun when she was but 18, because she learned that was her only route to India. While she loved her work and the camaraderie of the nuns, she slowly realised that her true vocation lay not in the security of the Loreto convent, but in the meaner streets and slums of her city.

The day was 5 September 1997. Thousands had gathered in Kolkata to say farewell to a nun who had completed her life’s mission. Her name had become synonymous with the conscience of that city. From the Netaji Indoor stadium where VIPs from all over the world had gathered to pay their respects, the funeral cortège proceeded slowly through streets crowded with mourners. It took four hours to reach Mother House, the headquarters of the worldwide Missionaries of Charity, the organisation that Mother Teresa had founded a half century earlier, and where she herself lived in a tiny room. Jyoti Basu, the formidable Chief Minister of West Bengal and the only person with whose name Mother used the prefix “my friend”, had acceded to the her Order’s request that her body be buried in Mother House itself.

Only about 300 Sisters of her mission could squeeze into the place. As her coffin was lowered into the grave, an unexpected VIP slipped in quietly. It was Hilary Clinton who wanted to be present at the funeral. Quite by chance, she came to be standing near my wife, Rupika and me. When a young Sister requested Mrs Clinton to say a few words, she spoke movingly of Mother Teresa’s extraordinary life of compassion and her wholehearted service to the poorest of the poor. As she looked around the room she also paid tribute to the Sisters of her Order when she said that in every face she saw, she recognised both the face and spirit of Mother Teresa.

Today, on her 111th birth anniversary we need to be reminded how and where she began her life’s work. She had enlisted as a Loreto nun when she was but 18, because she learned that was her only route to India. While she loved her work and the camaraderie of the nuns, she slowly realised that her true vocation lay not in the security of the Loreto convent, but in the meaner streets and slums of her city.

Advertisement

The Vatican gave her the extraordinary permission to step out, not as a lay teacher but as a nun with her vows intact. She was 38. She had no companion, no helper and only a five rupee note. Any large city can be a dangerous place. Kolkata had been ravaged first by the infamous famine and more recently by the traumatic partition of Bengal. Her early steps were very difficult. Between tears of longing to go back to the security of her beloved Convent, and heeding God’s call that he wanted her to help the poorest of the poor on the streets, she persevered. She kept a diary of the early months which I was privileged to read, wherein she wrote of her early hardships.

When a hospital refused to admit a man who was dying, she begged the municipality to loan her a disused hall near the Kalighat temple. Here she started a hospice where the abject poor, whom no hospital would accept, came. Hospitals were few and far between and did not want to offer a bed to someone most likely to die. Her inmates were rickshaw pullers and load carriers, many suffering from TB and malnutrition. Where was she to find them food and medicines? As she had no money, she taught herself to beg. She was often rebuffed. She would tell me over the years that for human beings the greatest fear is that of humiliation.

It was difficult but she learned to overcome this deepest of fears. Very soon people began to notice this strange looking woman. A nun yes, but not dressed in the habit of Europeans. Instead she wore a cheap white sari with blue stripes, similar to those worn by the municipal sweepresses. But people recognised goodness where they saw it. Some of her Loreto students joined her order as the first Missionary of Charity sisters. Volunteers flocked to help in little ways. It was then that Desmond Doig, a well known columnist for The Statesman began to follow her work. Nieces of Dr BC Roy, the then chief minister of West Bengal, volunteered to help.

Mother Teresa’s mission of compassion became a reality. We know where she left off. By the time she died in 1997, she had created a worldwide mission of compassion of over 600 institutions in 123 countries. She created shelters for the leprosy affected, Shishu Bhawans for abandoned infants and children, homes for the dying, old age shelters, hospices for AIDS patients when the disease was at its deadliest, feeding centres throughout Africa and Asia, and shelters wherever war and conflict was at its height.

Over the years I accompanied her to her Leprosy home in Titagarh near Kolkata and saw how deeply society had stigmatised the inmates. Nor was her mission confined to India. In London, I helped her Sisters distribute hot soup to the city’s homeless on a freezing night. And she helped demystify the Vatican by cajoling Pope Paul Two to give her a hall, where Rome’s poor lined up each evening for her Sisters served them their only hot meal of the day. Although a staunch and devout Catholic, she reached out to people of all denominations, irrespective of their faith, or even their lack of it. She did not believe that conversion was her work.

That is why people of all faiths were so accepting of this dimunitive nun. I once asked Jyoti Basu what he, an atheist and a Communist, could possibly have in common with Mother Teresa for whom God was everything.

He replied simply, “We both share in love for the poor”. When she was ill, he visited her in hospital as often as he could. When he was ill, she would lead a band of Sisters to his house to pray for his recovery. I feared that when she passed away the Order would shrink. But the opposite happened. Young women continued to join her Order. Nor did funding shrink. From India and the world, people contributed what they could. The Order expanded into 135 countries. Sister Prema, a nun of German origin, heads the Order.

She has refused to accept the title of Mother. The last two years that have ravaged the world with Covid have also caused the Sisters to comply with local regulations and slow down their street work. But as regulations are gradually relaxed in different parts of the world, they have restarted their work, stepping back on the streets to look after the destitute and those who have fallen by the wayside. The world lavished Mother Teresa with awards and medals. She was invariably received in the halls of power.

But that is not where her heart lay. I can do no better to conclude than by quoting John Sannes, then chairman of the Nobel Committee when he conferred on her the Nobel Peace Prize. “The hallmark of her work has been respect for the individual and the individual’s worth and dignity.

The loneliest and the most wretched,the dying destitute, the abandoned lepers have all been received by her and her Sisters with warm compassion devoid of condescension, based on her reverence for Christ in man… In her eyes the person who, in the accepted sense, is the recipient is also the giver and the one who gives the most. Giving – giving something of oneself – is what confers real joy, and the person who is allowed to give is the one who receives the most precious gift… This is the life of Mother Teresa and her Sisters, a life of strict poverty and long days and nights of toil thar affords little room for other joys but the most precious.”

(The writer, a retired IAS officer and former Chief Election Commissioner of India, is the biographer of Mother Teresa. His royalties have been largely ploughed back into the NGO he founded for children of leprosy patients)

Advertisement